October 10, 2025

Lighting Designers Confront Two Pressing Crossroads

Specifiers and manufacturers weigh in on growing tensions and solutions

Lighting, as a profession, has always flirted with permanence. Its best work is invisible, etched into the bones of a building, taken for granted until it fails. But at this year’s IALD Enlighten Americas 2025 in Tucson, Arizona, the people who specify the glow — architectural lighting designers mainly from across the U.S. and Canada — gathered with an increasingly uncomfortable question hanging in the desert air: what if permanence has become a liability?

Every year, the Lighting Industry Resource Council (LIRC) opens the conference with a facilitated brainstorm — a tradition that promises open collaboration and, sometimes, uncomfortable reflection.

The session unfolded in three facilitated brainstorms. One focused inward — on how IALD might expand its paid membership by welcoming professionals from adjacent roles like manufacturers, agents, and distributors. That conversation carries weight for the association’s future, but the other two topics — repairability and remote collaboration — cut closer to the daily friction points shaping the broader industry. That’s where we’ll focus.

The Razor Blade Problem

There was a time — not so long ago — when lighting was a best practice of the repairable economy. You could swap a fluorescent tube. Replace a metal halide lamp. Retrofit a ballast. Buildings ran on parts. But now, that logic is eroding.

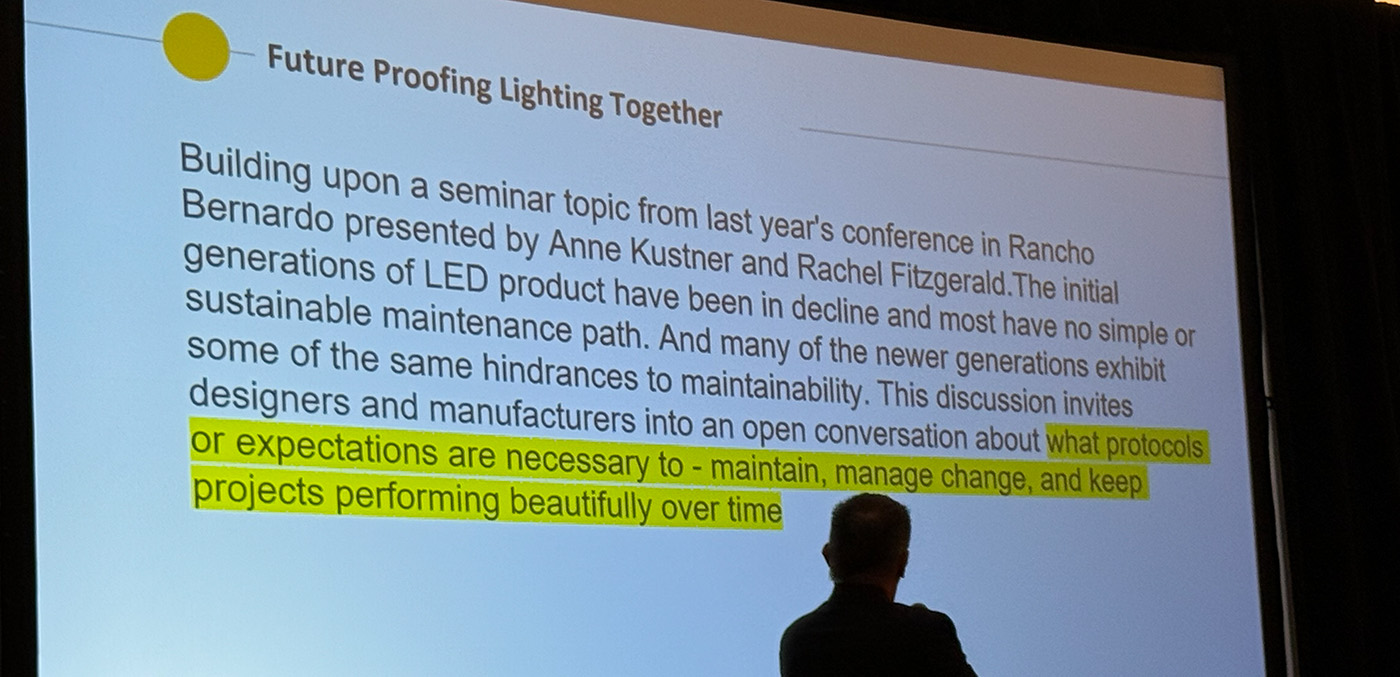

The second topic of the session — “Future Proofing Lighting Together” — was less a brainstorm and more a reality check. With drivers embedded and boards integrated, many modern architectural lighting products are, in effect, sealed units. Replace the light? Replace the fixture. Sometimes the ceiling. Maybe the wall. Imagine if every time your razor dulled, you had to buy an entirely new handle. That’s where we are.

This conversation didn’t emerge out of nowhere. It was raised last year on a stage at Enlighten Americas 2024, when Anne Kustner and Rachel Fitzgerald presented an exploration of long-term viability — and failure — of the first generations of LED products. The message reverberated in other places, including LightFair 2025 where Inside Lighting interviewed them on the topic:

Designers in the room didn't deny the progress of LED tech. But the group circled a painful reality: many of the gains — miniaturization, efficiency, form factor — have come at the cost of maintainability. If earlier lighting systems were modular, today’s are monolithic. Worse still, they’re being installed in long-life buildings that demand decades of performance.

IALD Influence Can Help Drive This

Some brainstorm groups suggested a path forward. Perhaps a position paper — crafted by IALD, endorsed by members — could push manufacturers to offer modular solutions. A consistent thread emerged: when lighting products are designed with repairability in mind, designers tend to hold their specifications more firmly. In other words, make the replacement path easier, and designers will become your strongest allies.

Standards Organizations Can Step In

Others floated the idea of third-party standards. Could NEMA, IES or UL step in and define what a “maintainable fixture” even looks like? Going one step further, could a baseline for LED module compatibility emerge — an Edison socket for the 21st century? That may be idealistic. Manufacturers operate more like the razor market — each with their own proprietary blade — and there’s little incentive to standardize when the margins lie in selling new handles.

Legislate

There was even talk of legislation. Could repairability be mandated? A distant goal, perhaps, but not unthinkable in a climate where Right to Repair has gained traction in other industries. The irony, of course, is that lighting used to be the original right-to-repair category. Most people over the age of 35 went to school under lighting systems that had been patched and re-patched over decades. Now, their children might sit under fixtures that have no defined end-of-life path at all.

Not everyone agreed a fix is still possible. Some attendees, including Paula Ziegenbein of Hartranft Lighting Studios suggested the window to influence product design has closed. The fixtures are already flying — literally and figuratively. But others think there is still a window to inspire change. If designers align on expectations, if they specify accordingly, if they make enough noise — there’s still time to steer the market. A little.

Above: Silhouetted in the foreground, session facilitator Ron Kurtz of Dark Light Design stands before a slide outlining one of the key discussion topics.

Whose Spec Is It, Anyway?

If the first issue was about hardware, the second was all business. It centered around the shifting dynamics of how remote lighting designers interact with local reps — and more pointedly, who gets credit for what.

Here’s the crux: lighting designers, like everyone else, are increasingly distributed. A junior designer might live in Denver and spec a job in Miami, with final sign-off from a principal in New York. And when that specification becomes an order, the manufacturer must assign “spec credit” — a term that ultimately determines who gets paid, and how much.

The room, which included a healthy mix of specifiers and manufacturers, agreed on at least one point: there is no consistent system. Sometimes, the local field rep who provides the samples, support is rewarded. Other times, they’re sidelined when the final spec is attributed to a firm’s home office in a different time zone. The friction went unspoken, but it hung in the air: if you’re a local rep unsure the return justifies the effort, do you keep showing up with the sample kits and endless spec support?

Designers want the support and it shouldn’t matter if they’re working remotely, juggling multiple projects. But they also don’t want to be entangled in opaque disputes about who gets what percentage of a spec. Most want to do the right thing, but the definition of that “right thing” varies widely. In many cases, reps submit their own records of support to manufacturers — email trails, sample requests, fixture schedules — effectively making their own case for compensation.

Inside Lighting has recognized this tension for a long time. We’ve even speculated about building a platform that could help untangle the credit conundrum. In fact, we’ve been sitting on the domain name www.SpecRegistration.com for years. But the issue is complex, and any third-party solution would face limits. So for now, we hold the domain — and keep watching the space evolve.