November 20, 2025

Bold Lighting Mandate to Reshape NYC Streetscape

City Council requires 1.0 footcandle sidewalk brightness across 300 blocks per year

New York City has enacted a sweeping new mandate that will change the look and feel of hundreds of streets. Passed in by the City Council last week, the new law requires the Department of Transportation to install pedestrian-oriented lighting on at least 300 commercial blocks per year beginning in 2027 — continuing each year until every commercially zoned block meets the City’s new brightness benchmark.

That benchmark — a uniform one-footcandle average across the entire sidewalk — places New York's sidewalks among the most aggressively illuminated in the country.

Behind every one-footcandle sidewalk will be trenches, poles, conduits, and procurement processes — on commercial blocks that might not have seen new infrastructure in decades.

The city's Office of Management and Budget estimates the mandate will cost $27 million annually

- Per-block estimate: $72,000 for construction + 25% for survey and design work ≈ $90,000 total per block

- 300 blocks/year × $90,000 = $27 million annually

- Four-year total: $108 million (with fiscal impacts that continue after year four)

90-second meeting, new law passed. Typical government efficiency.

DOT’s Warning Shot

In recent months, the debate over how bright a sidewalk should be quickly became a story about engineering, politics, and a clash between local legislation and national lighting standards.

At a June 2024 Council hearing, First Deputy Commissioner Margaret Forgione delivered the city’s strongest caution. The bill’s requirement, she testified, “proposes an extremely high and uncomfortable sidewalk lighting standard… too bright even for an expressway.”

Her point was not merely academic. She reminded the Council that DOT’s infrastructure footprint is enormous:

DOT is responsible for 6,300 miles of streets, 12,000 miles of sidewalk, and nearly 400,000 streetlights citywide.

Installing hundreds of new sidewalk-aimed fixtures each year, she said, would trigger widespread trenching and redesign. “Installing new light poles requires extensive survey and design work,” Forgione explained, “and often disruptive street excavations to lay new electrical conduits and cables.”

The IES Standards are Invoked

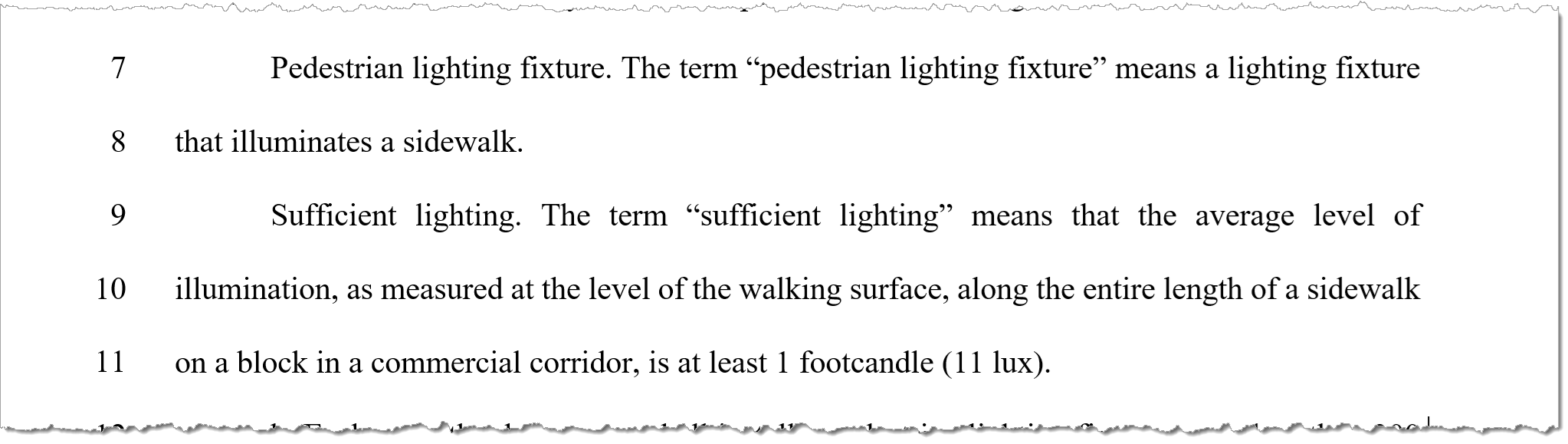

Forgione also noted that DOT already evaluates lighting based on IES RP-8, the industry’s consensus design standard — an internationally recognized playbook for roadway and pedestrian lighting. It is here where the engineering dispute becomes unavoidable.

IES RP-8 recommends the following for high-activity sidewalks:

- 10 lux average horizontal illuminance (≈ 0.9 footcandles)

- 5 lux minimum horizontal (≈ 0.5 fc)

- 5 lux minimum vertical illuminance at face height

- 4:1 uniformity ratio

These are minimum maintained levels — appropriate for busy retail corridors, transit hubs, and dense urban sidewalks. Specifying engineers often exceed them. But RP-8 explicitly warns that safe pedestrian lighting requires balancing horizontal illumination (seeing the path) with vertical illumination (recognizing faces, reading intent). Legislative bluntness, RP-8 suggests, is the enemy of good lighting.

A Mandate With Consequences

The City Council ultimately scaled the annual requirement from 500 blocks down to 300, but it did not soften the brightness standard. The law gives DOT little discretion: the footcandle threshold is fixed, non-negotiable, and must be met uniformly.

Supporters frame this as an overdue safety intervention, citing evidence that improved lighting reduces crime and increases nighttime foot traffic. Critics inside DOT counter that one uniform standard cannot account for the complexity of New York’s built environment.

New York now stands at the intersection of science and symbolism. The law promises a city washed in pedestrian-centric LED light. Whether it becomes a model of environmental design — or a case study in legislating past the engineers — will be clear in a few years, when the first 300 blocks shine on.