December 3, 2025

What If Your Lighting Simulations Are Wrong?

New research raises questions about photometric accuracy in industry-standard formats

For more than two decades, lighting specifiers have relied on the same fundamental approach to predict how installations will perform. Lighting design software has become the trusted standard, backed by industry leaders and used daily by thousands of professionals worldwide.

Photometric data flows from manufacturers into calculation engines that promise accuracy within tight tolerances. Projects worth millions of dollars proceed based on these simulations, and nobody questions the underlying assumptions — until the lights turn on and reality doesn't match the render.

But a peer-reviewed study published in LEUKOS last month suggests something troubling: under certain conditions, lighting simulation tools may not be as accurate as expected, due to legacy data formats that reduce complex luminaires to simplified point-source representations. The consequences aren’t purely academic. Some designers may already be encountering unexpected dark zones or glare problems that weren’t predicted by their simulation tools.

The Reach of the Problem

The researchers used DIALux and RELUX software applications — widely used in Europe — to model three types of luminaires and compare results against calibrated lab measurements. While the study focuses on these two platforms, the underlying issue lies in the structure of standard photometric file formats. That raises an open question: if AGi32 and Visual in North America also rely on IES file formats with similar geometric assumptions, could comparable simulation errors be present across all major platforms?

The LEUKOS paper doesn’t test those North American tools, but it does highlight fundamental limits in how traditional file formats represent spatially complex luminaires. As such, it’s reasonable — though unconfirmed — to consider whether the challenge extends across the board until enhanced data formats are more broadly adopted.

A Closer Look at the Errors

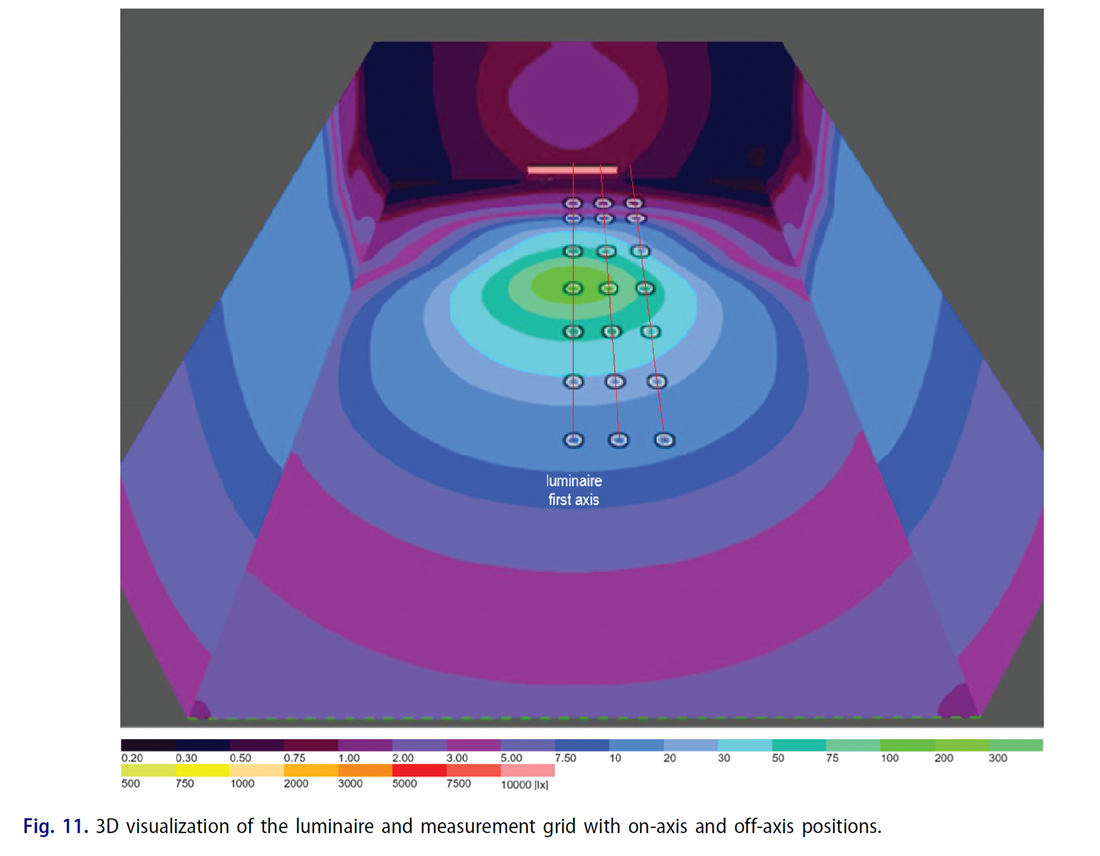

The research, led by Marek Mokran at Slovak University of Technology, tested three luminaire types against laboratory measurements. For compact fixtures, DIALux and RELUX delivered relatively accurate results — deviations stayed within 2–6%. But for luminaires with multiple spatially separated light sources, errors rose sharply. In one tested configuration, deviation exceeded 30% at a 1-meter offset — a scenario not uncommon in certain classroom or office settings. Even standard linear luminaires showed consistent 6% deviations at one-meter off-axis positions, which often correspond with task surfaces.

To be clear: not all typical installations will suffer large errors. The most significant deviations appeared in near-field regions (within ~1 meter) and with specific luminaire geometries. At standard mounting heights around 2.5 meters — typical in offices — the study reports that deviations often fell to within 1–2% for linear fixtures. But the potential for larger errors remains, particularly when designers rely on simulations involving complex luminaires at close range.

Above: Excerpt from "Simulation Inaccuracy in Lighting Design Caused by Geometric Assumptions in Luminaire Data"

The Format Problem Nobody Talks About

The root cause isn’t a software bug — it’s a structural limitation of widely used photometric file formats. Both the IES (.ies) and Eulumdat (.ldt) formats were developed decades ago under assumptions suited to simpler lighting technology. These formats typically assume far-field conditions and are not designed to capture the spatial complexity of modern LED luminaires with non-continuous or modular emitting areas.

As a result, real-world luminaires with non-emitting gaps or physically separated modules may be flattened into a single, smoothed abstraction. The software appears to treat these as uniform surfaces, producing renderings that look more seamless than the actual luminous environment. Researchers describe this as a kind of “pseudo-near-field correction,” though the study does not confirm the specific algorithms in use.

At mounting heights of 2.5 meters or below — a common scenario — this simplification can break down, especially in luminaires with more spatially distributed emitters. Whether these approximations are built into the software intentionally or emerge from file limitations remains unclear.

What the Study Does (and Doesn’t) Say

The study avoids alarmism. It recommends that designers “be aware of possible inaccuracies in near field regions and reflect this in the design process.” It does not suggest the entire industry is designing blindly or using tools that are universally unfit. Rather, it offers targeted evidence that in some design scenarios — particularly with non-uniform luminaires at short distances — simulation tools can deviate in meaningful ways from real-world results.

It’s worth asking: are current workflows accounting for this possibility? Or are designers assuming a level of fidelity that isn’t always there? The study invites scrutiny, not panic.

Questions Around Liability and Simulation Integrity

While the LEUKOS study doesn’t weigh in on regulatory or legal implications, its findings raise questions. If lighting simulations lead to unexpected glare or non-uniformity, and those conditions compromise code compliance or visual comfort, where does responsibility lie? Could there be cases where narrowly passed simulations lead to real-world conditions that fall short of performance requirements?

The study also mentions that luminaire definitions in data files can involve larger emitting surfaces than physically present — a practice that, if widespread, could affect UGR calculations. It stops short of suggesting intent or identifying specific manufacturers. Still, the potential for discrepancies between modeled and real-world glare may prompt designers to ask whether simulated UGR ratings can always be trusted at face value.

What’s missing, researchers note, is transparency. Many software platforms don’t openly document how they handle spatial data distribution or near-field approximations. That opacity makes it hard for specifiers to assess which luminaires and which tools might be more susceptible to simulation mismatch.

Where the Industry Goes from Here

Enhanced photometric data formats that incorporate near-field spatial measurements already exist — but they’re not yet standard. Until that changes, designers face a decision: continue to rely on familiar workflows that may miss near-field inaccuracies, or build in validation steps to confirm that simulations match reality in critical applications.

The authors of the LEUKOS study suggest a middle path: deliberate oversizing in simulation when near-field conditions apply, and empirical checks for projects where uniformity or glare control are especially sensitive.

The study doesn’t claim that the sky is falling. But it does shine a spotlight on a blind spot. Whether that becomes a call to action — or just another unsolved quirk of lighting design — remains to be seen.